REGENERATIVE RELIQUARY

2016

26 in H x 18.5 in W x 24.5 in D

Artist Amy Karle creates artwork using the body to explore what it means to be human through a unique negotiation of art, design, science and technology.

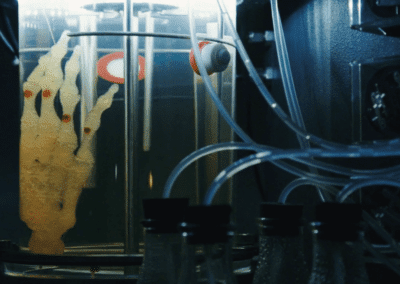

Leveraging the intelligence of human stem cells, she created “Regenerative Reliquary”, a bioprinted scaffold in the shape of a human hand design 3D printed in a biodegradable pegda hydrogel that disintegrates over time. The sculpture is installed in a bioreactor, with the intention that human Mesenchymal stem cells (hMSCs from an adult donor) seeded onto that design will eventually grow into tissue and mineralize into bone along that scaffold.

Inspired by the generative and parametric design in the body, this piece considers how cells articulate into different forms – what makes a cell become a beating heart, skin, or bone – in naturally occurring “additive manufacturing” created by a multiplier effect. “Regenerative Reliquary” further focuses on the dynamic organ and tissue in our bodies that is constantly remodeling and changing shape to adapt to the daily forces placed upon it: bone.

Bone is the structure and foundation that supports our bodies. It seems solid, but bone is very much alive and constantly changing. Bones are a material of life as well as a material that is left after death; historically used to make tools, accessories, art and objects. Throughout history, there has been a spiritual, macabre, and even miraculous agency associated with bones. Bones have been enshrined into reliquaries to serve as memorials, guidance, protection, objects of fear, superstition and devotion.

Referencing the traditional presentation of relics in their reliquaries, this piece is a finely detailed skeleton sculpture encased in a glass bioreactor. Instead of enshrining the inanimate remains left after death as a memorial to the life that was once there, “Regenerative Reliquary” presents the opposite, depicting the possibility of life from an inanimate object.

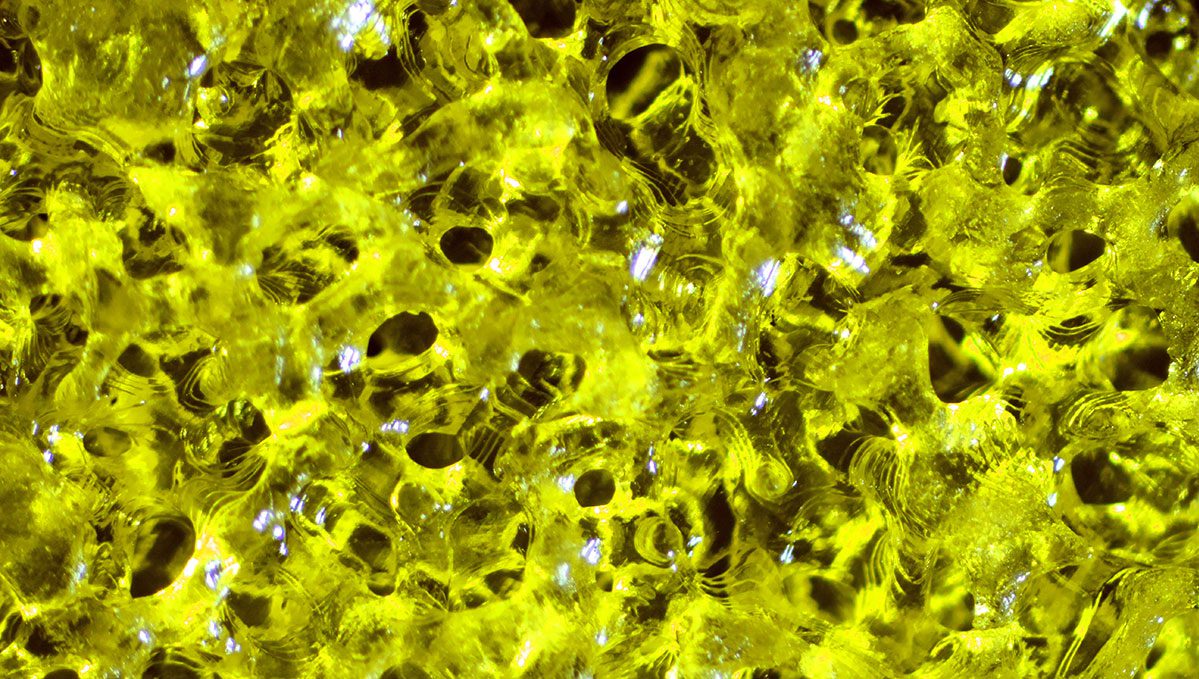

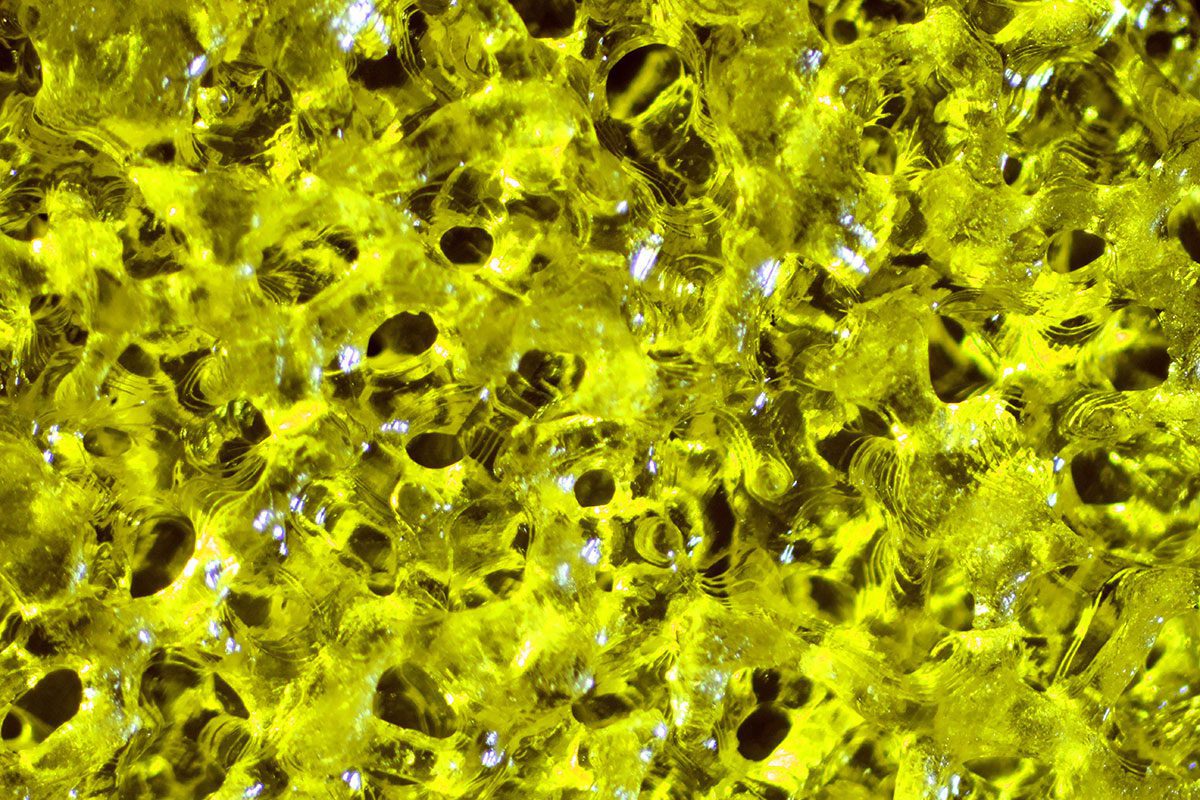

Housed in a mechanical womb of scientific equipment, the human hand-like design appears to glow from within, lit from the interior and reflecting out into surrounding darkness. Conceptually, the human hand design was selected because this part of the human skeleton is one of the few structures that is instantly recognizable as uniquely human. The ornate aesthetic was derived from functional design requirements: the overall lattice was created for biomimetic osseointegration; on the microscopic level the scaffold mimics the trabecular structure of bone, the shape that triggers stem cells to become bone cells. The distinct yellow color of the sculpture was required in order to 3D print with such detail in a biodegradable, biocompatible material. Although this specific sculpture is intended to live outside of the Although this specific sculpture is intended to live outside of the body, the design suggests that future versions could potentially be implanted and integrated with existing biological features.

This relationship to the piece as human-like catalytically raises questions about what it means to be human: how we may potentially grow existing and new human forms, how this concept and approach can be applied to healing and augmenting the body, what we may use human cells to create that is not human, what new forms we could design and grow with cells, and if human cells are used does that mean the new piece is now human?

“Regenerative Reliquary” made artistic, scientific and technological advancements as it required and inspired new innovations to be made in its creation, as well as influences a new way of thinking. Using cells and 3D printed scaffolds is a new medium for art and design. Advancements in both software and hardware were made to process and digitally fabricate the extremely complex geometry, which needed to be 3D printed on the microscopic level in trabecular form, roughly representing the geometry of the number of cells in real human hand bones. The piece required new materials to be developed and made: to stereolithography (SLA) digital light process (DLP) 3D print this large scaffold using non-toxic biodegradable materials that cells could grow and thrive on without timing out, sustainable, biofriendly materials that could foster cell culture and be 3D printed with microscopic detail were developed and made for this piece. Pioneering collaboration with scientists and technologists resulted in innovation in all fields. At the time of this sculpture’s creation, this piece was the largest 3D printed scaffold for stem cell growth known to be made internationally. Karle’s bioart work established a new field in the art world, expands opportunities for biomedical applications, healing and enhancing our bodies, and opening minds to create things that were never possible to create before.

“Regenerative Reliquary” encourages envisioning both medical and artistic futuring, fostering innovation and education. This piece may serve as a foundation for further exploration and research, and to open conversations about transhumanism, synthetic biology, the future of medicine and implants, speculative design and things that could be made from cells both inside and outside of the body. Karle said: “We are at an exciting time where we no longer need to turn to inanimate materials like metal, fabric, or paint to make an object. We can use actual living cells and tissue as materials to build with. The cell, “nature’s building block” can be the basic structural unit”. She shares her workflow to create 3D printed scaffolds open source as a platform for exploration and development of this line of work by scientific and artistic researchers alike.

The hand design was in part inspired by persons with limb differences. Karle volunteers creating 3D printed prosthetics for children with an upper limb difference through E-Nable, Kid Mob and Superhero Cyborgs. “I was envisioning a leapfrog technology to regenerate anthropomorphic limbs for their medical purposes. If this application is developed, the potential healthcare benefit is that a patient’s own stem cells could be used for a personalized bone graft”.

Although Karle created this piece as artwork for outside of the body – not intended to be implanted, if this application is developed, the potential healthcare benefit of this approach is that a patient’s own stem cells could be obtained and used for culture, remodel onto a personalized bone graft designed to be an exact fit out and implanted with low risk of rejection since it is made out of their own DNA, and without complications of foreign implantation. A patient’s own cells provide for better integration also because it is living, has the potential to continue growing and remodeling in the body.

The concept of regenerative medicine was also influenced by Karle’s childhood friend who is battling Pulmonary Hypertension, in need of a double lung transplant and a therapy for scarring of her bone marrow caused by the same medicine that is keeping her alive. Karle said: “I began envisioning a future factory where the same materials – just a few cells, could be used to grow organs, marrow, limbs, and also create art and design objects, even technology for both inside and outside of our bodies… a sustainable factory with low waste, where minute amounts of material can be grown into many different forms, reconfigured and reused for many purposes to enhance and enrich our lives”.

SPONSORS

This project was made possible with the generous support of Autodesk, Autodesk’s Pier 9 Artist in Residence (AiR) Program, Bio/Nano Research Team, the Ember 3D Printer Team, Within Medical, Autodesk Software and Evangelists, California Academy of Sciences, Exploratorium: The Museum of Science, Art and Human Perception, and The Bone Room.

COLLABORATORS

Thank you to the collaborators who generously contributed their knowledge and talent to this project:

Bio-Nano Scientist Chris Venter

Material Scientists John Vericella and Brian Adzima

FILM by Charlie Nordstrom, Assistant Editor Blue Bergen, and Amy Karle

https://vimeo.com/amykarle/bringingbonestolife